The Exotic Subject

Words by Thais Diniz

Graphics by Levi LoCascio-Seward

Sometimes I wonder if Brazilian femininity was designed for export.

We are expected to be sensual, expressive, effortless—always glowing under the tropical sun, as if born with highlighter on our cheekbones and rhythm in our hips. But for many who don’t fit the mold, beauty feels less like a blessing and more like a battleground.

Fernanda Young wrote once, “I shaved my head for eleven years, purely as punishment. I wouldn’t allow the feminine. I didn’t want to appear delicate before the world, because I thought the world would hurt me.” The impulse to shut down vulnerability before it can be weaponized is familiar.

In Brazil, being too delicate means being prey; too hard, punished. Too smart, too queer, too Black, too fat, too quiet—the algorithm doesn’t know what to do with you. Unless, of course, you make yourself consumable.

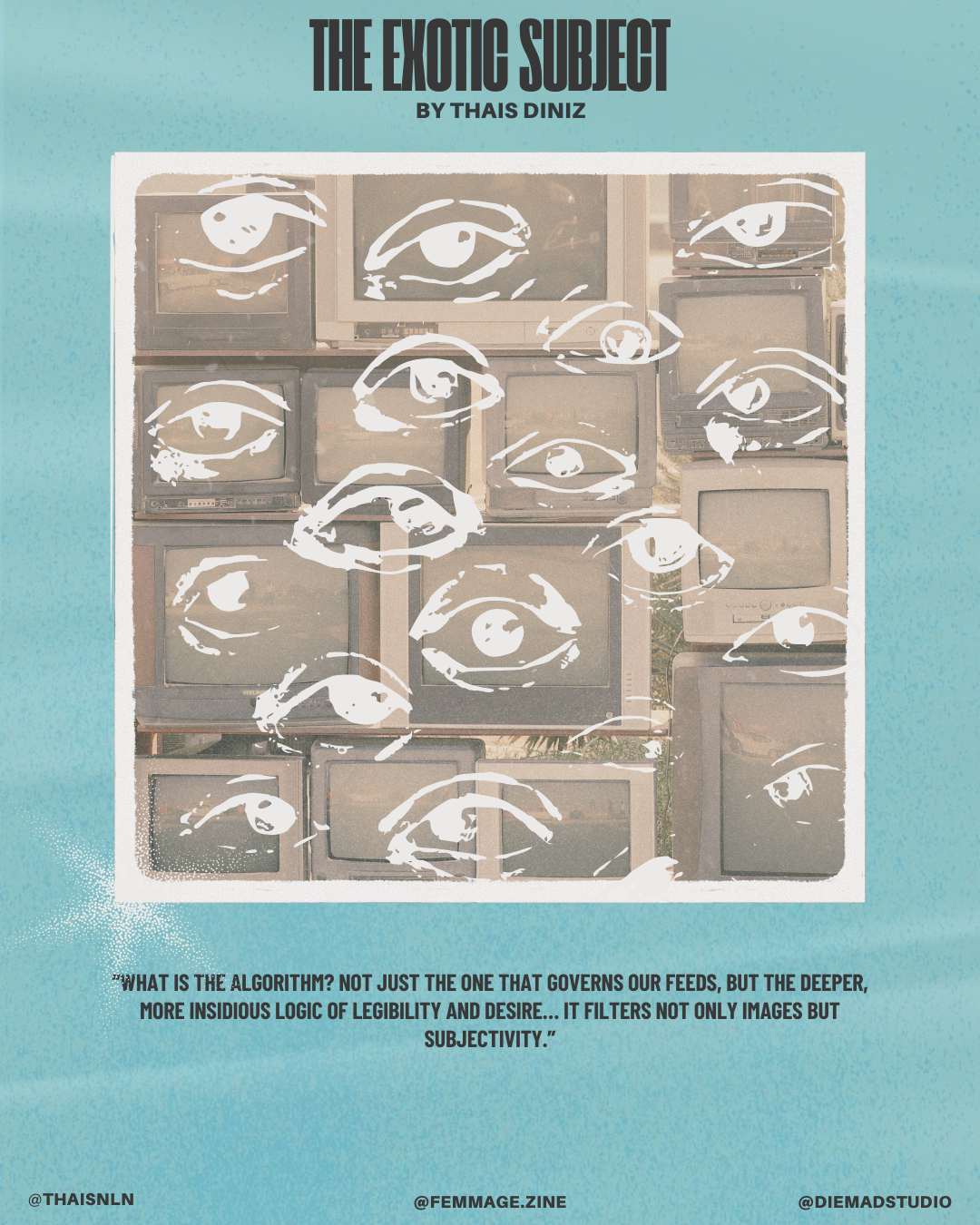

But what is the algorithm? Not just the one that governs our feeds, but the deeper, more insidious logic of legibility and desire—how society instructs us to be seen and wanted. It filters not only images but subjectivity.

Susan Sontag described femininity as performance art. What happens when the audience is faceless and infinite, and applause is measured in likes? Margaret Atwood warned that under patriarchy, “you are your own voyeur.” The algorithm makes this literal, colonizing the gaze from within.

Jean Rhys wrote of women who collapse under the pressure to be lovable. Clarice Lispector let them crack silently, mid-thought. Annie Ernaux turns memory into a weapon. None made themselves easy to read.

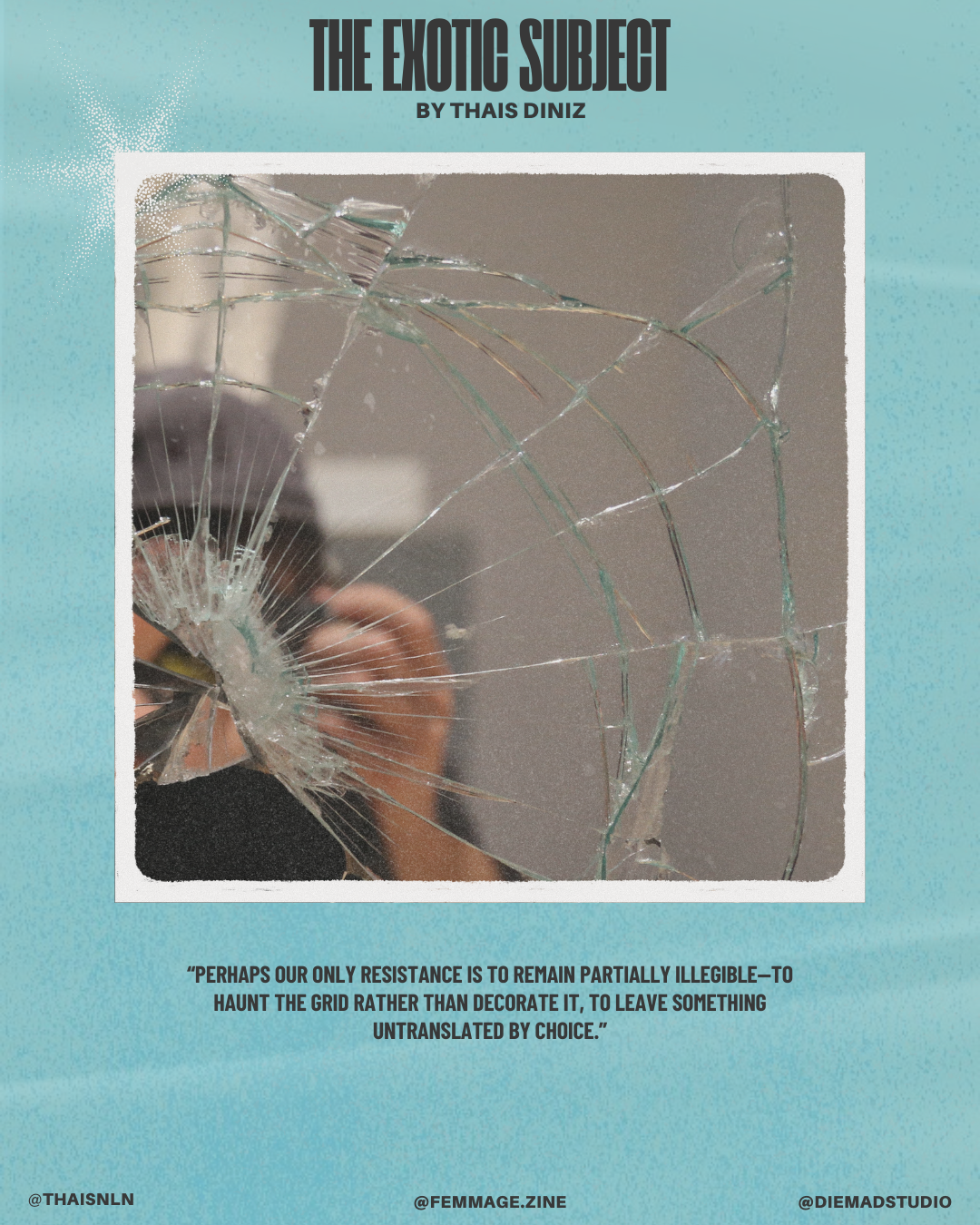

Perhaps our only resistance is to remain partially illegible—to haunt the grid rather than decorate it, to leave something untranslated by choice.

So we contour, dance, tweet with humor, cry through filters, bleed a little—but never enough to break the frame. We lip-sync to Sabrina Carpenter, reference Beyoncé, laugh at trauma while pretending it heals. But beneath it all, we carry other layers.

We move like Maria Bethânia in Reconvexo — multiple, syncretic, unapologetic. Proud to blend the rhythms of Santo Amaro with Rome’s streets, Candomblé’s drums with jazz’s pulse, brega with global pop.

Brazil is the world’s most racially mixed country, a living tapestry of Indigenous, African, European, and immigrant ancestries (according to Pew Research Center and IBGE). This rich miscegenation shapes not only our bodies but our culture—our music, our language, our digital selves. Our online personas are not borrowed aesthetics but celebrations of integration, a refusal to be either/or. We hold contradiction as a badge of honor.

We don’t speak Spanish, so we watch the world from outside — too Latin to be North American, too Americanized to be fully South American. When our first film won an Oscar, it felt like a cultural paradigm shift—like the world finally saw us.

Still, the question lingers—as Tim Bernardes sings in “Meus 26”:

“Mostrar o mundo pro Brasil ou o Brasil pro mundo?”

Should I show the world to Brazil or Brazil to the world?

That question haunts me. Perhaps we have been performing for the wrong audience. Perhaps that’s why our digital selves feel like fractured translations—trauma turned trend, longing turned likability.

Sontag warned against suffering as spectacle — a polished image detached from its rawness. Online, vulnerability is curated, trauma a motif, longing flattened into a surface shareable by millions.

Clarice Lispector’s work reminds us that beneath every post, every filtered selfie, lies an ineffable core resisting easy translation. The Hour of the Star captures the tension between performative self and “real” self, the isolation of inner life that often escapes the gaze.

We crave to be seen and understood, but the language of likes and trends is a fractured mirror—reflecting surface glimmers but missing depth, contradictions, and silence. The algorithm sees only outlines and glitter, not the fractures beneath.

We learn to be understandable in another’s language, beautiful in another’s filter.

Then I fell for a man who embodied the algorithm in human form—a clinical gaze, a Californian soul.

In the tangled landscape of love and identity, I met someone who was everything I resisted—and still, I wanted him to want me.

He’s Brazilian by birth but American in posture. Raised under the California sun, trained to dissect minds, he speaks Portuguese like a half-remembered melody — familiar but distant. He tells me Brazil is wild, our people too emotional. That I remind him of the women he treated in American prisons — intense, unstable, poetic. As if those were medals, diagnoses, verdicts.

I’ve never broken a law, never worn a prison uniform. What he means is clear: I am too much too feeling, too loud, too alive. But in his world, feeling must be tamed, expressed in approved doses, in ways that do not disturb order. There’s a dangerous excess in how he sees me—reducing a vast, messy landscape of emotion into symptoms to be contained.

Perhaps, in a twisted Lacanian irony, that’s why I was drawn to him—the fixer of what he deemed broken. I became the enigma he couldn’t solve, the wildness he couldn’t cage. I mistook his clinical gaze for true knowledge.

His logic is analysis over affection, detachment over devotion, freedom over care. Yet he kept coming back—perhaps because I glitch, refuse to be optimized.

And I? I kept watching myself through his eyes. Wondering if I performed the right kind of wounded beauty—desirable but not too much, sad but interesting, Brazilian but exotic, American but coherent.

—

What does it mean to be witnessed by a machine—when the machine is a man who diagnoses your soul?

A man older, with more power, who knows too much, who sees too clearly.

He speaks from his place—white, Brazilian-American—with the weight of knowledge and the silence of possession.

Maybe that’s why I let myself be his object.

Because the unknown is safer than the known.

Because being desired is a form of being seen, even if it means being reduced.

Sometimes, being a woman here—online, in love—is like performing for a camera that never stops.

Translating myself again and again.

But I have Venus’s left hand holding mine.

What’s left behind the filter is not an abyss.

It’s something beyond the glitch, beyond the girl.

It’s human potency