Situationships and Emotional Bankruptcy

Words by Talisa Gray

Graphics by Anjoli Trinidad

Key Terms

Situationship : A term used to describe a relationship that lacks clear commitment or definition, often characterised by ambiguous emotional involvement or a lack of long-term intent. It typically involves sexual intimacy but avoids the responsibilities or expectations of a romantic relationship.

Hyper-sexuality : The cultural or psychological tendency to prioritise sexual activity

Hyper-Individualism: A cultural phenomenon that priorities personal autonomy and self-sufficiency

Epilogue

A phantom taste coats my gums, salt and rejection sliding down my throat. It’s unpleasant and unthinkable, and it’s exactly what it reeks of. That sudden realisation that I’ve been used for sex. I’m walking away from the café as quickly as my feet will carry me, desperate to flee the scene, her gaze burning my back the whole way. I’m praying she can’t see how my body racks with quiet sobs. I’m praying she doesn’t think she hurt me, doesn’t think this mattered to me (of course it does.)

She doesn’t want a relationship. Naturally, it’s taken two months of seeing each other to come to this conclusion, and naturally, such a realisation only springs to mind after we’ve slept together.

A tale as old as time.

Of course, as situationships go, this (now) ex-lover had no issue holding me while I slept, kissing me on the forehead, bringing me flowers, meeting my friends. She had no issue leaving in the night, as I would half-heartedly cover my bare chest, ignoring the way my hair stuck to my face, lipstick smeared. Her smile always half-embarrassed, but not quite apologetic, as she slipped into the night, not sparing me even a ofference of water or (unthinkably!) reciprocation.

This ex-lover, does however, take issue (as so many do!) when I dare to clarify whether this ‘thing’ between us is headed toward a relationship.

We were sitting cross-legged in my bed, both exposed, hair damp from showering together. She’d come to my soccer game just an hour beforehand, awkward but polite, introducing herself to my friends as my… well, just as her name. She’d come to watch me play, in support. I’d, stupidly, taken this as a sign she liked me.

What's the new adage? “Silly me! I thought he liked me because he said he liked me.”

I hadn’t even intended to ask that night, half-knowing what the answer would be. The question had slipped out between my clenched teeth before I could think to snatch it out of the air.

It still makes me cringe, thinking about how quickly the smile had died from her face, heavy eyebrows drawing into a frown over her big brown eyes. It was stifling. Awkward. Unpleasant.

At the café just a week later, we’d sat awkwardly shoulder to shoulder. I remember staring at her green cargo pants, seeing the stains and food crusted on the sides. She hadn’t even bothered to wear a clean outfit for this. The realisation of just how little I meant to her stuck with me. She couldn’t even bother to wear a clean outfit when I’d done a full face of makeup, painted my nails, changed my outfit three times—just knowing I'd see her, despite knowing what was likely coming that day.

The brown-eyed girl folded her hands in her lap, chipped nail polish interlocking.

“I want to want this. I do. But I just don’t want a relationship right now. I think we should be friends. I’d really like to be friends.”

Hyper-Individualism: The Commodification of Emotion

In a world that prizes individualism above all, we are left to navigate a landscape that celebrates detachment and self-sufficiency. We are conditioned to believe that relationships are nothing more than transactional—something that can be picked up and discarded at will, with no true emotional commitment required. This is how situationships thrive: a phenomenon that has become so normalised that it no longer surprises us when someone proposes that they only want “friendship” after a prolongued intimate encounter. This detachment is rooted in the fear of vulnerability, the belief that connecting too deeply with someone risks emotional harm.

Here’s the paradox: in an age of hyper-connectivity, we’ve never been more alone due to the rise of hyper-individualism. The more we chase self-sufficiency, avoiding emotional vulnerability to protect ourselves from pain, the more we reduce others’ emotions to commodities. We treat them as things to be consumed or used for convenience. Nowhere is this more evident than in the proliferation of situationships, where intimacy—particularly sex—is cheapened into a quick fix to fill the emptiness left by a lack of real connection. It’s a way to fill the void without the mess or risk of true emotional engagement. This phenomenon speaks volumes about how far we’ve strayed from meaningful connection.

In this landscape, “friendship” is perverted. We use people for emotional or physical satisfaction but still claim we’re “just friends.” This blurring of boundaries between platonic and sexual relationships is not an accident, but a product of a society that places more value on individual autonomy than on mutual emotional trust and connection.

Hyper-sexuality: The Erosion of Meaningful Intimacy

On the other hand, the pervasive sexualization of our culture is directly tied to the detachment we experience in relationships. Sex has become a commodity—something that can be exchanged freely in the marketplace of connections. Social media, advertisements, and now interpersonal relations are overrun with hyper-sexual content. Consider something as simple as a TikTok "outfit" video and how these videos have become routinely sexualised. Consider how pervasive and brain rotting such non-stop access to pornographic material is. How many Tiktok (or Instagram reels if that's your thing,) OOTD (Outfit of the day) or GRWM (Get ready with me,) videos begin with a man in his boxers, grabbing his masculinity while trying (and always failing) to subtly flex every muscle in his dehydrated body, or similarly, a beautiful woman intercuts her weekly ‘what I wore to work’ outfits with snippets of her scantily clad in push up bra and thong. I’m by no means trying to slut shame, or act as some kind of prude. You’re young and beautiful—enjoy it, post it, profit off it. But that’s my point. Why is almost every facet of media I turn to so oversaturated with sexuality? I wanted to see how to pair my red tights with a mini skirt, not to see another glowing six pack.

This normalised commodification of sex is reducing our brains and attention span to a pile of goop wired for one thing: pleasure. Five years ago I’d have been aghast that every other video on my phone demonstrates some person in some form of undress, but it’s just so normalised today I don’t even bat an eye. The “sex sells” mantra has become our cultural currency and, in the process, has undermined the idea of sex as something deeply personal and meaningful.

The widespread acceptance of such a hyper-sexualized culture has made intimacy feel disposable. In many cases, people have learned to disconnect their emotions from sex, viewing it as a casual activity devoid of lasting emotional consequence. The result? Situationships—temporary, uncommitted encounters where a couple behaves as though they are in a relationship, without actually being in one. An interpersonal dynamic where people engage sexually and romantically without the responsibility or accountability demanded by an actual relationship. We pretend that this is freedom, but it’s not. It’s just another form of emotional avoidance, a perversion of the romantic.

The Perversion of the Platonic

The most troubling part of this new norm is how it distorts what we once understood as platonic connection. Plainly, if we’ve had sex, we cannot be “friends.” We’ve crossed into a territory that demands a different emotional engagement.

The line between platonic connection and sexual entanglement has become so blurred that I often hear people describe those they’ve slept with, or continue to sleep with, as “just friends.” This mislabeling commodifies intimacy, turning it into a transactional exchange where pieces of ourselves are offered emotionally or physically, but the emotional debt is buried behind the false title of “friend.”

The term friend in such a context is a fallacy. Friendship, in its truest form, is not meant to be a container or vessel for sexual escapades. True friendships require boundaries—an understanding that, though there may be deep emotional intimacy, there is a line that should not be crossed. Once sex enters the equation, a connection cannot be platonic again, the line is fundamentally altered.

If I’m being honest, I’ve started asking people a question at parties, half-drunk, definitely slurring and probably with more than a few tears in my eyes:

“Do you have a friend you’d sleep with if you were drunk?”

If the answer is yes, that’s not your friend. Friendship isn’t built on that kind of ambiguity. It’s about clear mutual respect, not the possibility of something more. Friendship should never carry the weight of "what if." Hyper-sexuality, with its focus on instant gratification and detachment, feeds into these blurring of lines. We’ve been conditioned to think that sex can be casually separated from deep emotional engagement, but this only creates confusion and emotional dissonance. When you can imagine crossing that line with a "friend," it signals a lack of boundaries, and a normalisation of transactional, shallow connections that fail to honour the emotional depth that true friendship requires.

To put it bluntly: once sex is involved, it’s no longer a friendship. It’s something else, something that carries emotional complexity and risks. Would you be comfortable with your romantic partner being best friends with someone they’ve slept with? Most people wouldn’t, because shared intimacy denotes complexities and feelings and connection. Yet, we think we can pretend these complexities don’t exist in our so-called “friendships”.

This problem is compounded by the larger cultural narrative. We've been conditioned to believe that emotional detachment equals freedom. Labels like “just friends” or “friends with benefits” offer a way to avoid the messiness of commitment while still getting emotional or physical satisfaction. But that detachment is an illusion.

In these relationships, one person may be attached, unwilling to let go, while the other hides behind a socio-cultural “get out of jail free” card offered by such false labels, avoiding emotional responsibility. Friendship allows us to breathe—no strings attached, no deeper commitment, no culpability.

The tragic reality is that both sides of these relationships are left emotionally bankrupt. One person might be desperately holding onto the idea of “just friends” because they don’t want to risk a deeper emotional investment, while the other person might be pretending that their feelings don’t matter, even though they do. And both of them, in some way, are complicit in the erasure of genuine emotional connection. There’s no intimacy in pretending we can engage in something so deeply emotional without facing its consequences.

In my own experience, I still find myself in contact with people I’ve been intimate with, clinging to the faint hope that they might, one day, pursue me the way I deserve. I continue to hold onto the title of “friend” despite the emotional baggage we share. They knew I wanted to be their girlfriend. They knew, they balked, and they—with a pathetic lameness—offered me the flimsy title of friend. A wilted, pathetic olive branch that I took in shaking hands and pretended not to notice the massive “fuck your feelings” etched into the side.

This is the real tragedy of the situation. It’s not the physical encounters themselves; those are relatively simple, though no less impactful. It’s the emotional dissonance we are left with afterward. We are left pretending that detachment is liberation, that distancing ourselves from the emotional messiness of connection is somehow a strength. The truth is, it’s a slow burn of emotional destruction. We are told not to feel, not to care about the strings that tie us together in moments of intimacy. But the truth is that we always care, even when we claim we don’t. And when we deny that emotional weight, we risk becoming hollow. We risk our values. Our self respect, dignity, and at least in my case, self worth.

Concluding: The Lie of Detachment

How can we devalue the depth of intimacy, the vulnerability, and the emotional exposure that comes with love, and yet expect it to exist without consequences?

As Kafka once said, "I was ashamed of myself when I realized that life is a masquerade party, and I attended with my real face." That’s what this all is: a masquerade where we pretend that detachment is a form of strength when it’s just another way to hide from the messiness of true emotional connection.

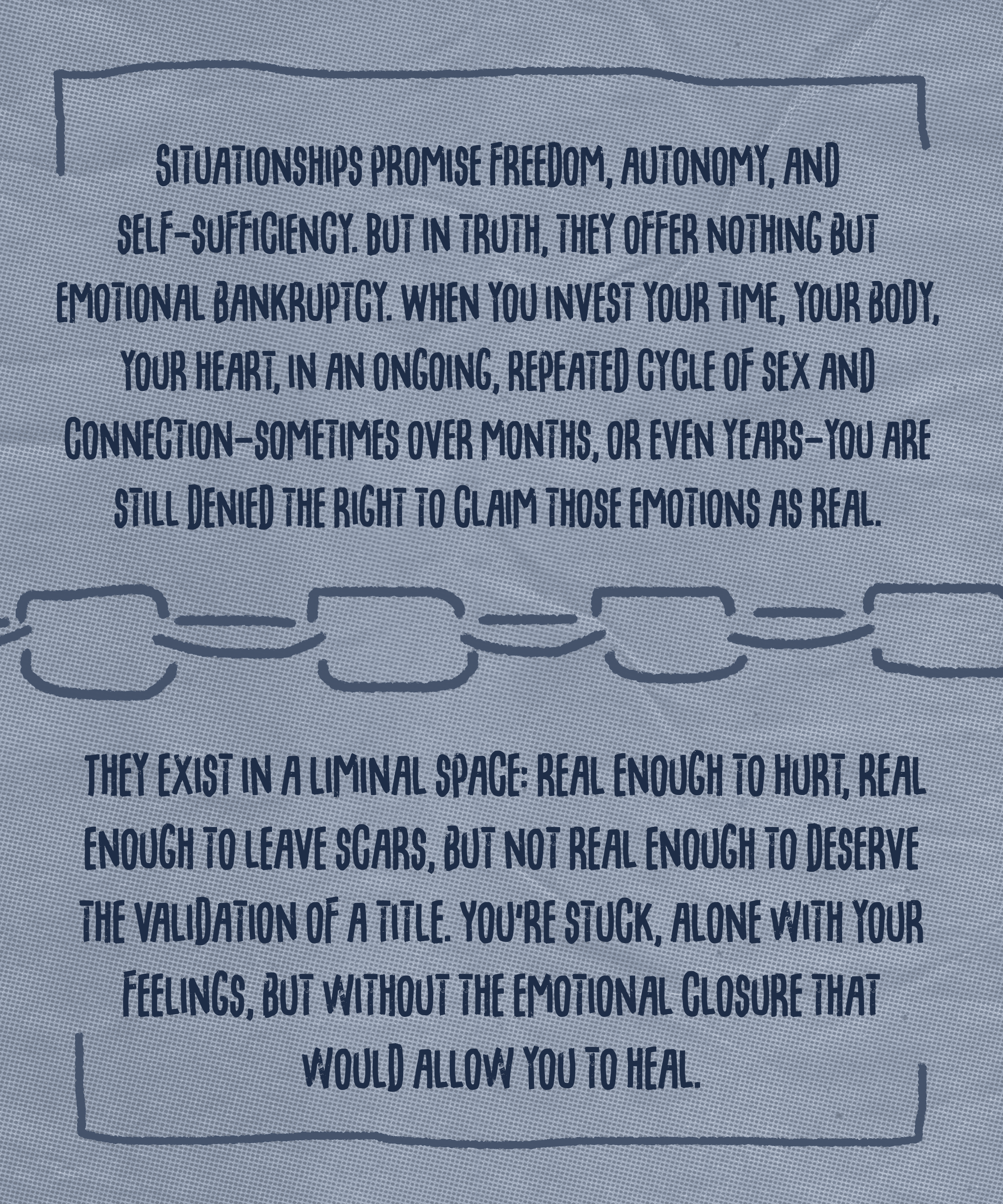

Situationships promise freedom, autonomy, and self-sufficiency. But in truth, they offer nothing but emotional bankruptcy. When you invest your time, your body, your heart, in an ongoing, repeated cycle of sex and connection—sometimes over months, or even years—you are still denied the right to claim those emotions as real. They exist in a liminal space: real enough to hurt, real enough to leave scars, but not real enough to deserve the validation of a title. You’re stuck, alone with your feelings, but without the emotional closure that would allow you to heal.

We’ve been sold the lie that emotional detachment equals strength. That by avoiding commitment, we are freeing ourselves from the messiness of emotional investment. But you can’t have intimacy without vulnerability. You can’t share your body and soul, over and over again, without facing the risks of emotional entanglement. In situationships, it’s not just the sex that becomes complicated—it’s the feelings, the expectations, the hurt. To separate sex from its emotional consequences is to treat both like empty transactions, like moments to be consumed and discarded without acknowledgment of the toll they take.

But, like most people, I played along. I agreed to the ‘friend’ label, even as I felt that ball in my chest squeeze a little tighter. I was convinced it would be ok. After all, we didn't even date!

I remember laying in my bed, thinking about the stains on her jeans from the cafe. The phrase, “I want to be friends,” ping-ponging around my head.

Ironically, I had been dramatically listening to Sarah Kinsley’s “The Giver” on repeat, “He turns around when you’re naked, says we should be friends while you're changing…”

When my phone had pinged, a message from her.

“Hey Pal…”

I couldn’t help but snort at the absurdity of it all. Yeah, sure. Pals.

In that moment, as I lay there, red eyes staring incredulously at the text (as “The Giver” played, again), I felt that pit in my chest open a little wider.

We keep playing this game, pretending that emotional detachment is liberation, but it’s not. It’s just the slow unravelling of everything we crave, the quiet erosion of what it truly means to connect.